About

CLEOPATRAS – CLEOPATRAS

Staging may adopt multiple forms. In the second half of the 1980s, CLEOPATRAS chose to present themselves according to the disposition, gestures and collective appeal of a band, although they did not have instruments nor songs. Rather, theirs was theater crossing over into other expressions; especially music (and vice versa). This was a convinced and colorful live dynamic, full of provocation; through which its four members plotted an autonomous feminine manifesto, unprecedented in the country, and whose features are still an influential and valid contribution.

At a time when Chilean independent art was adopting the solemn forms imposed on resistance creation, CLEOPATRAS conceived a protest that was wrapped in popular codes and seductive signs. It was an unexpected transgression —and therefore, unforgettable.

| PATRICIA RIVADENEIRA: «If silence prevailed, we were the noise. Part of a chosen family, an artistic movement that brought together musicians, filmmakers, actors, dancers, painters, poets and writers united by the desire to break taboos, find spaces of expression, manufacture ideas, create new languages, give free rein to experimentation, denounce repression, seek air and beauty, save us from the silence and isolation that were being imposed. It was a vigorous, intuitive, concrete and Dionysian movement, and it transported us to the center of life: to be and to evolve.»

TAHIA GÓMEZ: «What we did had a ‘pop’ appearance, yet an elaborated background. We looked to the outside, discussing ideas and perfecting ourselves in a particular way, since there were no referents here for what we were interested in. Who were you looking at then in Chile? Where did you nourish yourself? Collective depression and fear: that was all there was.» |

In front of a microphone stand, four stylishly beautiful women with striking gestures declaim (original) texts of brief and forceful sentences, like hit choruses for a non-existent band. Among the enclaves of a Santiago with movements regulated by an anchored dictatorship, CLEOPATRAS’ presentations escape a theater company’s conventions, although they don’t exactly qualify as performance nor music recital either. Issues in their plays, their interpellation to the audience and numerous quotations taken from the pop imagery unfold, to the spectators’ perplexity, in a dynamic of their own, from the concept to the staging.

| CECILIA AGUAYO: «We bet on the massive, thinking that our texts on stage were like songs —which would be listened, memorized and get repeated. We did not want passive spectators.»

TAHÍA GÓMEZ: «I used to say: “Let’s pretend we are a band…”. But not so we could play songs, but to send a message to people. We were not theater, performance nor music; but rather something that had never been done before. We couldn’t define ourselves as one thing —although our vocation was definitely popular. We wanted to show a kind of work that people would participate in. To raise a message along the lines of, “Come out! Get out of where you are!”.» |

Time has surrounded CLEOPATRAS’ collective memory with blurred images and quite a few misunderstandings.

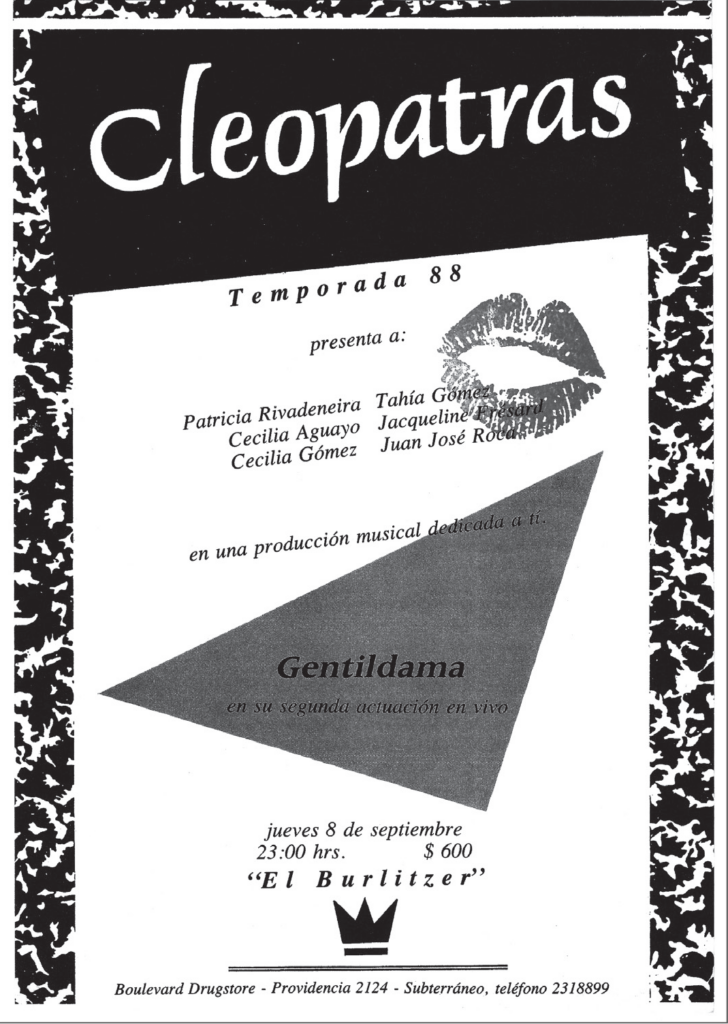

Since the late 80’s, the key facts about their birth and evolution have brought together the ideas of women involved in performing arts outside of Chile’s official circuit. They made their debut in January 1987 at the premises of a production company (Publicine), at Constitución Street (in Santiago’s Bellavista neighborhood). «A musical production of women, dedicated to men», invited the poster of Cleopatra, chicas del Nilo, a play vaguely inspired by a Shakespeare tragedy (Antony and Cleopatra) to metaphorically challenge opprobrious attitudes in the country at the time, like the craven fascination with Augusto Pinochet as an authoritarian figure (represented in Marco Antonio, Roman emperor, played on stage by José Barrenechea), the dazzling glitter of the new economic order imposed by the so-called “Chicago Boys”, and the persistent subjugation of women to social roles designed to their disadvantage.

This first staging responded to Patricia’s interest in the stories of classical antiquity, as well as to Tahía’s interest in texts anchored to a certain discomfiting sonority, able to cross eroticism, irony and criticism of hierarchies.

| TAHÍA GÓMEZ: «We spoke to men and, through them, to power. Historical men and our contemporaries; those we despised and those we loved. Where is power? How do you get to reach it? What does power do with me? Never as victims, and each one of us with her musicality.»

PATRICIA RIVADENEIRA: «In such a ‘macho’ context, the feminine then had no space. Even the artistic world of the time was patriarchal, and viewed us with sarcasm… and appetite. Faced with that, we used seduction and humor; as a self-ironic exacerbation of the feminine that was, nevertheless, serious. We put our private world in the public, using all of our bodies’ weapons. The challenge was to overcome coyness and expose ourselves. Being vulnerable strengthened us.» |

Jacqueline Fresard, an Art student with a background in theatrical design, had previously collaborated with the group in costumes and scenography. Her joining outlined CLEOPATRAS’ definitive formation for a second staging, Cleopatras – temporada 88 (at the “Burlitzer” theater, in Providencia).

New productions were to come, always sporadic, until 1992 (including the invitation given to the group by Vicente Ruiz for his version of Antigone, a year earlier). The «Cleopatras style» combined distinctive features, such as the display of their scripts as if they were appeals to the audience (and not dialogues among characters), in montages that sought the viewer’s coparticipation; as well as a postmodern aesthetics, influenced by pop bands such as The B-52’s and Bananarama (remotely related to the one that in the post-Franco period had also uncovered in Spain the so-called «movida»). Young women, of refined manners and a rather conservative family upbringing, willing to let their own vital and artistic experimentation define the creative process to which they sought to adhere.

«With no censorship nor fear», they say.

The group’s was a continually evolving narrative, of unique setups and no repetition. Of exhaustive study and extensive discussion, backed by hours and hours of rehearsal, as they recall; as well as a work concept that also ventured into visual and technical innovations (with the use of closed-circuit cameras, the projection of photographs, slideshows, etc.). «It was like a live videoclip», as they defined it in interviews.

Their talents and studies converged: Patricia as director and dramaturg; Tahía in choreography and concepts; Cecilia in music and dance; Jaqueline in visual display.

«We are the best, there are no others out there. We have a different aesthetic proposal», they introduced themselves in their first press feature.

| JACQUELINE FRESARD: «We thought of ourselves as very modern, despite how uncertain everything was back then. Our plays were ambitious, and I took on that visual challenge with no budget at all, but no fear either. It meant going against prejudice. We liked things that others considered tacky; learning to work creatively as a team, attending each other’s visual expectations.»

CECILIA AGUAYO: «Ours were not overly polished montages, due to the great technical precariousness that we worked with; but they were ambitious, and not in a commercial sense, but in terms of artistic result. We were not interested in displaying any particular rhetoric, but rather working in a bolder way, based on our intuition and rebelliousness, looking to show well nourished works. We had had many ideas, and with no money, managed to materialize them with the help of many friends.» TAHÍA GÓMEZ: «The artistic elements that we incorporated into our work were frowned upon by the Theater scene. We were told that our work was deficient, frivolous, that we lacked technique. But then ten or fifteen years later those same elements could be seen in the productions of important directors, which made us realize that although we were misunderstood, we were never that lost. There was no interest in reaching the intellectual world, neither the elite theater scene, nor the critics. We were neither erudite nor politically correct.» PATRICIA RIVADENEIRA: «It was an unsettling proposal for that time, because it did not respond to the conventions of Theater, show business nor feminism as they were understood until then in Chile. However, we were not looking for a place to belong. We had a certain forward-looking boldness, given to us by our youth and lack of experience. The restoration of democracy was soon to impose new rules, and the leaving of that type of experimentation. What we did was adapted to a specific moment in which we wanted to participate critically in our own way.» |

All of CLEOPATRAS’ presentations had songs or musical pieces performed live, which were specially composed for their shows, with lyrics related to the contents (most of them, written by Patricia Rivadeneira). Several musicians who where then active in Chilean bands (Archie Frugone, from Viena; Juan José Roca, from Paraíso Perdido; Rafal Guiñez, from Parkinson; and Daniel Puente, from Pinochet Boys) contributed their voices and instruments. The recurring collaboration of María José Levine (Upa!), stands out because of her background as an actress, dancer and musician.

At the height of his popularity with the group Los Prisioneros, and captivated by the suggestive proposal of the quartet, Jorge González contributed songs such as “Cambia”, “Noche” and “Corazones rojos”; the latter, written precisely from memories and descriptions of the four CLEOPATRAS about experiences of patriarchal imposition, and according to the vocal pulse of rap that was heard in their plays. The famous singer-songwriter also accompanied them in their studio work and in their project —never fulfilled— to record their first LP. Many things joined the quartet with Los Prisioneros’ leader; among them, a shared inspiration towards the Latin American romantic songbook, that which the audience makes theirs as a direct hook straight to the heart.

| TAHÍA GÓMEZ: «We were aware of the power of female seduction, and so we loved to show it. We never defined ourselves as feminists, and were not bothered if somebody labeled us as sex objects. We never believed that pleasing a man meant being in a servile position, on the contrary. We were feminine, and we denounced sexual harassment in our own way; for example, by mimicking the proposals for sex in exchange of a job, so that the motherfucker who had asked would feel exposed. What we were fighting against was not gender roles but passivity. The enemy was that submissive female role imposed by Catholic morality, and which was expected of us according to our origin and social class. Somehow, we wanted to say: that’s not going to happen to us.» |

| JORGE GONZÁLEZ:

«I keep beautiful memories of the times when we recorded these songs. Santiago was going through a hopeful era. Eventually, what we expected didn’t happen, but feeling that illusion was still nice. CLEOPATRAS taught me to learn, to forget, to ignore. Each one of them, with a voice that fully matches her personality. The fact that they were not “professional singers” was creatively refreshing. Working with them, besides being a pleasure, was one of my life’s creative moments that I treasure the most. Their different and complementary personalities allowed me to embrace melodies and lyrics that, on my own, may not have existed. Without further ado, let’s listen…” |

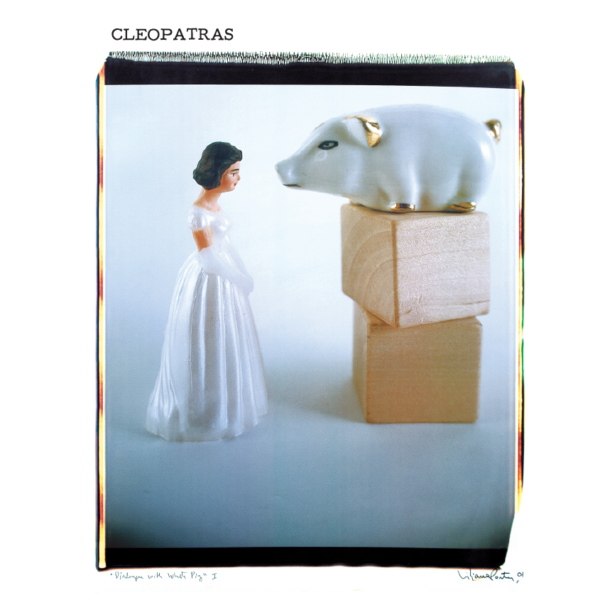

| The recordings of some songs and vocals from CLEOPATRAS’ stagings (1987-1991) were released for the first time in 2016, on an LP published by Hueso Records, with technical supervision by musician and producer Uwe Schmidt, a.k.a. Atom™. These are non-professional tracks, captured on stage and/or taken from demos, the most relevant of which is the 1988 demo for “Corazones rojos”, with vocals by Jorge González, Tahía Gómez and Cecilia Aguayo, and some verses different from those that would later become popular in Los Prisioneros’ version. This new edition of the album, of 250 copies on vinyl, keeps the original material and adds “Peonía roja”, a composition from the band’s foundational period, recorded in 2024 by Cleopatras and Entrópica, a Chilean electronic artist. The artwork belongs to Liliana Porter.

This CLEOPATRAS album is part of a collaborative project between Hueso Records and ISLAA (Institute for Studies on Latin American Art), which seeks to present music of resistance to the military dictatorships imposed in different countries of South America during the 70s and 80s. It highlights the inventiveness, talent and strength of a type of political protest through creation, which managed, with very limited resources, to express itself against the repression and censorship of the arts in the region. Each disc in the series is linked to the submission of visual artists specially contacted for this project, whose images evidence the friction between disciplines, as well as the distinctive character of a geographical area in particular historical circumstances. |