About

Chile was then a country of few colors. Muted tones and imposed shades dominated the landscape, caught between military olive green and a gray that matched the fear of daily life. But from the early 1980s onward—in successive band projects, collaborations, and finally as an independent sister-brother duo—María José and Sebastián “Tan” Levine kept composing songs that were both acts of resistance and declarations of brightness, rhythm, and energy. In a country subdued by a dictatorship and paralyzed by mistrust, their music stood out.

«Many young people at the time settled into the gloom, which is why we identified with post-punk and its introversion. We created MARÍA SONORA as a contrast to all that. We felt it was time to venture into music that wasn’t so serious or so sober —looking for something playful. Our concerts were colorful, almost kitsch. The idea of color and rhythm was like a manifesto.»

It wasn’t the first time the Levine siblings had collaborated —there had been the band Primeros Auxilios (1984–1985) and a theatrical version of Hipólito, directed by Vicente Ruiz in 1984— but MARÍA SONORA became their most distinctive project. Despite limited promotion and few recordings, it left an indelible mark. From its inception in 1988, the duo set out to blend rarely combined Latin and North American rhythms: hip-hop, funk, raggamuffin, cumbia, rock. Their performances featured professional musicians and striking visuals.

In a country where artistic creation was then often born as a form of resistance, MARÍA SONORA’s music was not a direct denunciation, but rather an invitation: to celebrate tradition (“the calypso rhythm that runs through my veins / runs through my brother’s veins, and my mother carries it!”) and to reconnect with the body (“I’m feeling the heat you left floating / flying, spinning around my room”), while staying alert to the threats then surrounding them (“…we are always out of place / evicted from the kingdom. / […] We are the fallen children / the possessed angels, / the thinkers of the illegal / provocateurs of the abnormal”).

One magazine at the time called them «the ultimate musical seduction, rhythmic above all else. MARÍA SONORA is destined to become a sensation on Chilean dance floors.» Another described their audience as follows: «The party is coming. The sparkles grow more enticing, and the compadres are waking up from their lethargy.»

María José and Tan Levine reached these high-energy songs —whose lyrics seemed to spring from a fervent pagan faith— after a long creative journey, key to the map of 1980s Chilean music shaped in the self-managed circuits of Santiago. These were years of harsh repression, but also of creative ferment. From a young age, both had crossed paths with bands of different styles, and this cross-pollination only intensified as their generation realized that political dissent had to find new forms —through aesthetics and interdisciplinarity.

She had played with Cleopatras, and was a prominent vocalist, keyboardist, and co-writer in Upa!; he had worked as drummer, producer and/or sound engineer for a dozen bands, including Los Pinochet Boys, Electrodomésticos, La Banda del Gnomo, and La Goma de Pegar (a short-lived collaboration with Los Prisioneros’ Jorge González).

«Around 1983, when the first protests against Pinochet began, there was already a kind of creative effervescence. There were people who now wanted to do something, despite the lack of resources or role models. Musical ideas were circulating —punk, new wave— and many of us were willing to adapt them.»

But this time, it was different. MARÍA SONORA had its own blueprint, with fresher and broader references than those typically seen on the live circuit they frequented: university venues, nightclubs near San Cristóbal Hill, and old warehouses in Santiago’s historic neighborhoods (such as the legendary El Trolley).

A nearly two-year trip to Brazil in 1987 —where Tan studied Afro-Brazilian percussion— exposed him to genres then little known in Chile: hip-hop, Afrobeat, and new currents in industrial and funk. María José, meanwhile, was emerging from her most visible years with Upa! into a new phase of experimental and autonomous creation —her first time leading a project that demanded both her vocal versatility and magnetic stage presence.

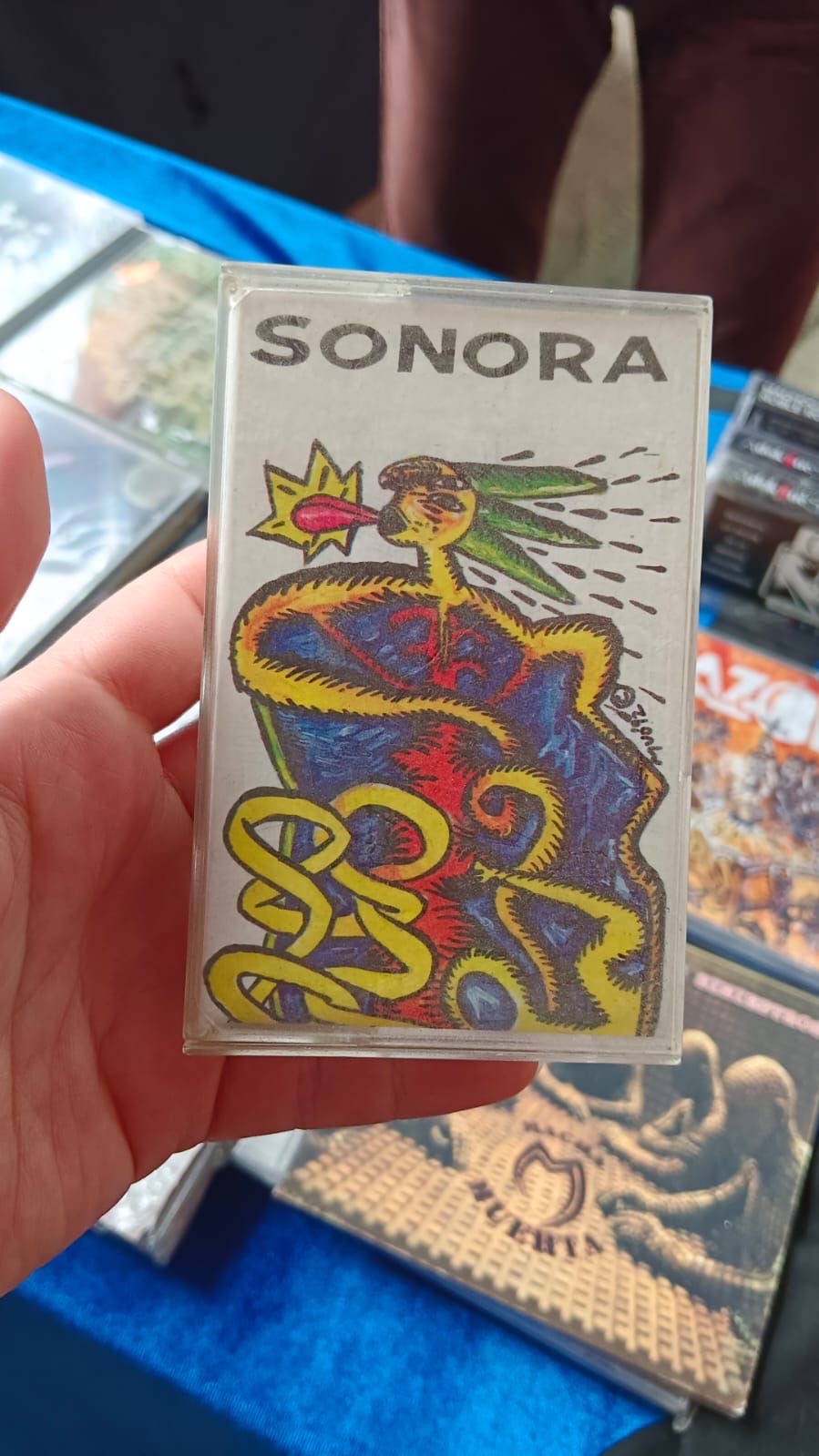

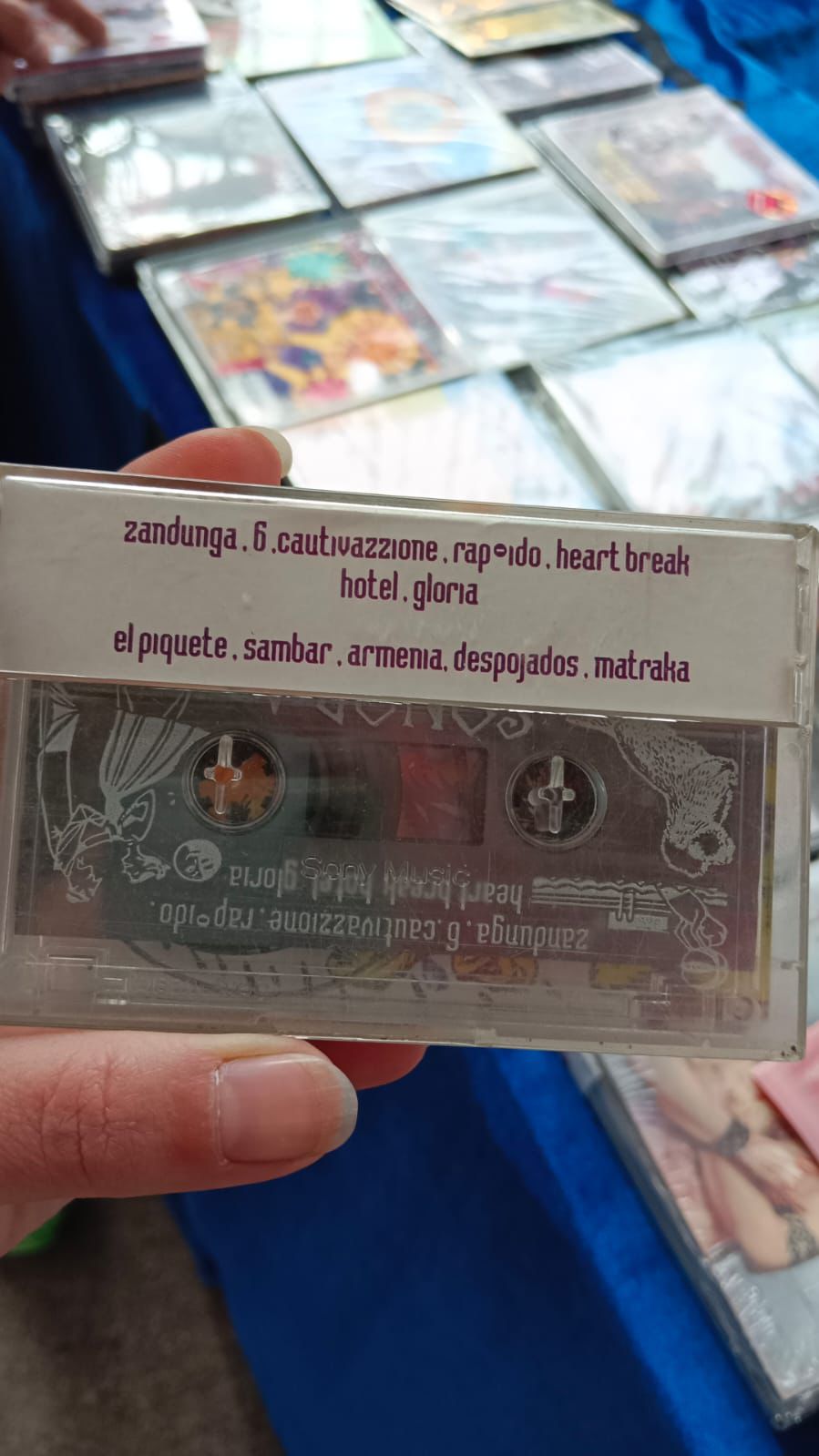

MARÍA SONORA’s first album was an exceptional work, though surrounded by setbacks that ultimately kept it from being released. Recorded in Santiago over more than a year (1989-1990), it featured acclaimed musicians then active in bands like Los Tres and Electrodomésticos. With a strong presence of brass, keyboards, and percussion, the tracks made room for layered sequenced sounds. All the songs —except for an intense cover of “Heartbreak Hotel”— were written by the Levine siblings, finely balanced between traditional instruments and electronic effects.

An unexpected deal with the Japanese label King Records opened the door to international possibilities. In early 1991, María José, Tan, and co-producer Carlos Cabezas traveled to Tokyo to mix the tracks recorded in Santiago. Working in technical conditions unlike anything they’d seen before, they completed a polished and agile production. But back in Chile, just as the local music industry was entering a post–pop boom decline, MARÍA SONORA couldn’t find a label to release nor distribute the album. Only a few handmade cassettes remained as mementos of this ambitious work —one that foreshadowed what would later be called electronic cumbia.

From then on, the group entered intermittent stages. Around 1992, the addition of three musicians on bass, guitar, and turntables brought a rock edge to their sound —another early crossover anticipating what would later be known as nü-metal. A major concert at the National Museum of Fine Arts in January 1994 marked the beginning of their farewell, sealed by Tan’s move to the United States. The next decade brought two attempts at reunion: first under the name Golosina Caníbal, which released the album Kru-da in 2000, and later as a trio with a digital release (Cumbia Calling, 2011).

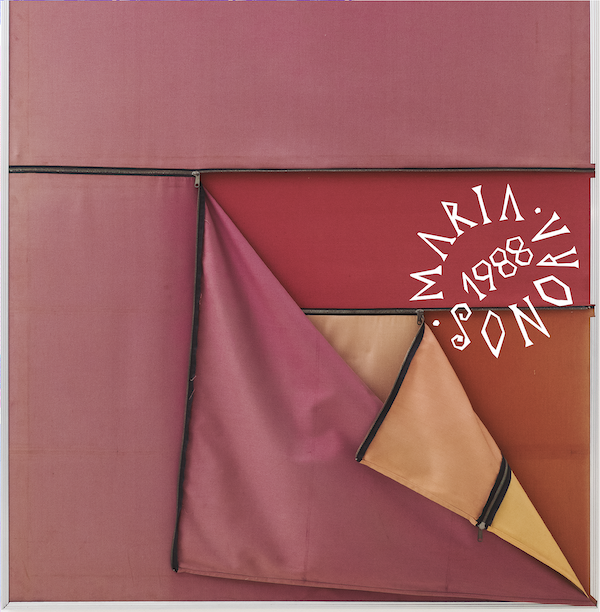

It all began with that unreleased LP; now, 36 years after its recording, finally presented by Hueso Records, with remastered original tracks and cover art by Brazilian artist Nelson Leirner.

***********************************************

MARÍA JOSÉ LEVINE is a Chilean singer and songwriter with a background in dance, opera, piano, sound therapy, and a degree in Philosophy. Since her teenage years she has been involved in a wide range of music and theater projects. In Chile, she is best remembered as the lead singer of the pop group Upa! (1987-1988), where she also played keyboards and co-wrote songs, including the hit “Río río.” She later joined Primeros Auxilios, María Sonora, and Golosina Caníbal; recorded backing vocals for Viena and Pinochet Boys; and contributed vocals, songwriting, and production to projects and musicians such as Cleopatras, Eduardo Peralta, Paraíso Perdido, Orquesta de La Pampilla, and Cristián Cuturrufo, among many others.

«Although I had already played in bands, the challenge with María Sonora was starting something from scratch. That’s where I really began taking on new roles: as a frontwoman, a producer, and the one making all the practical decisions. Of course, I drew on what I had learned with Upa! and from being in a well-known group. But working with my brother was different — more fun, easier, without obstacles. It gave me space to grow, not in a solemn way but through creativity and play. I remember it as a constant search for new sounds, an ongoing exchange of ideas, and the good fortune of being surrounded by talented people. That independence required effort too, since we were a duo and had to do everything ourselves. María Sonora always had this paradox: the less seriously we took ourselves, the further we went. That’s how we ended up with a record deal in Japan and even the chance to travel there. Waiting so long to finally release it… and doing so now, under circumstances we never imagined… it still amazes me.»

SEBASTIÁN “TAN” LEVINE is a Chilean drummer, percussionist, composer, sound engineer, and producer. From his teens onward he has been part of numerous self-managed and avant-garde rock bands, either as a member or collaborator. These include Pinochet Boys, Electrodomésticos, La Banda del Gnomo, Primeros Auxilios, La Goma de Pegar, Blancoactivo, Los Marginales, Carlos Calor, Supersordo, and Aceite Humano. He also played in the band that backed Jorge González on his first solo album after Los Prisioneros, and has worked as engineer or producer on recordings by La Pozze Latina, Los Peores de Chile, Parkinson, Índice de Desempleo, and more.

«My path with percussion has been long, always influenced by rock since I was a teenager. But in the mid-80s I discovered techno-industrial music that fascinated me — bands like Test Dept, 23 Skidoo, Yello, Hula. Dark, experimental sounds mixed with ethnic rhythms, which I found incredible. That shaped me a lot. When I moved to Brazil after Pinochet Boys, I studied Afro-Brazilian percussion with Mestre Dinho and bought congas. Back in Chile in 1988, it sounded completely strange. No one was mixing pop with electronic sounds and genres like hip-hop or cumbia. Friends would say, ‘What is that stuff you’re listening to? That’s not real music…’ At that point, among the twenty projects I had going, María Sonora gave me the chance to play hip-hop live — and that was perfect! Even if other bands later cited us as inspiration, I don’t think of it as taking credit, just a fact: we were making music that hadn’t been done before in Chile. The band was a mix of everything I was into at the time (Blanco Activo, Aceite Humano, Pinochet Boys, Electrodomésticos…) fused into this cocktail of sound and live energy, with colorful costumes onstage. We looked good, we sounded good — pretty cool, right? But it was also a stagnant time for music in Chile. There wasn’t much room for a project like ours. Bad luck, really, to fall into the gap between two waves of mass popularity, which left us on the outside.»

VOICES FROM THEIR PEERS

Carlos Cabezas (Electrodomésticos):

«María Sonora was very innovative for the time. The stylistic mix they proposed at the start of Chilean rap was remarkable — colorful, but not calculated, more like a natural space they created for themselves where urban styles and musical crossovers worked without pretension. Both brought rich experience: Tan with his percussive explorations and the Afro-Brazilian influences he brought back, and María José with a strong, distinctive voice. Between siblings, their music felt playful, effortless, rooted in the essence of artistic expression. It was fresh, curious, and ahead of its time. To think that this album was made 35 years ago in Chile… it’s remarkable.»

Jorge González (Los Prisioneros):

«Their album is full of surprises: timbres combined in unusual ways; metal guitars that seem out of place but fit perfectly; percussion that’s playful and joyful. A party! I was lucky enough to see them at the legendary Casa Constitución around 1988. They were unlike any other band. I still remember Tan in cycling shorts, rapping obscenities, while Jose, elegant and poised, sang. Maybe their sound was too playful and unusual for that time. Now its moment has come — though the album is still just as playful and unusual.»

Pedro Foncea (De Kiruza):

«It’s an album I love — very diverse. The sound and use of samplers were far ahead of its time. Eclectic and refreshing, and that’s why it has lasted.»

Silvio Paredes (Electrodomésticos):

«Back then, collaborating with friends was part of daily life. I met Tan through Javiera Parra, since they were classmates. We played together in Primeros Auxilios, later in Aceite Humano, and then I recorded for the María Sonora album, while I was also playing in Electrodomésticos. At the same time I was moving into visual arts and design, and the band asked me to help with graphics. We turned limitations into creativity — making photocopies visible, playing with cut-outs, collages, flat colors. We did fun, inventive stuff.»

Cuti Aste:

«I first met Tan when we were both guests with Electrodomésticos, and he later invited me to join the band with his sister. I recorded three songs on soprano sax and accordion, and also joined some live shows, while I was performing in La Negra Ester. We rehearsed on Maturana Street, in Yungay, where musicians, painters, and theater people all lived and shared ideas. I admired Tan’s talent. He gave the band a unique sound, mixing electronic and pop bases with touches of the tropical and the oriental. There was digital timbaleta, sequenced bass, and Jose’s voice… very novel, very worked out. But no record remained. No album, no revival, nothing. They were like the anti-band.»